Pandemic restrictions have caused misery in low income countries

Background

Since Covid-19 broke out in Europe in later Winter/early Spring of 2020, radical non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) have been used in many countries to supposedly limit transmission. These were undertaken quickly and in a panic which may have been understandable in the first weeks of the outbreak. They have remained to this day in much of Europe in one form or another without good quality evidence they are of any benefit. Despite the dubious nature of these NPI measures even in Europe, they have also been copied almost wholesale in many African countries. This is regardless of their very different economic resources and population age profiles. The disastrous effects of these measures have already become plain and the repercussions will likely be seen for years to come. As early as 2020 a study by two professors at the Karolinska Instituet analysed data from UNICEF and UNAIDS and concluded that least as many people have died as a result of the restrictions as have died of Covid directly. The causes of these deaths will be malnutrition, caused by shutting down economies, lower vaccination levels for childhood diseases and reductions to treatment of endemic diseases like malaria, tuberculosis and HIV.

Population age profile

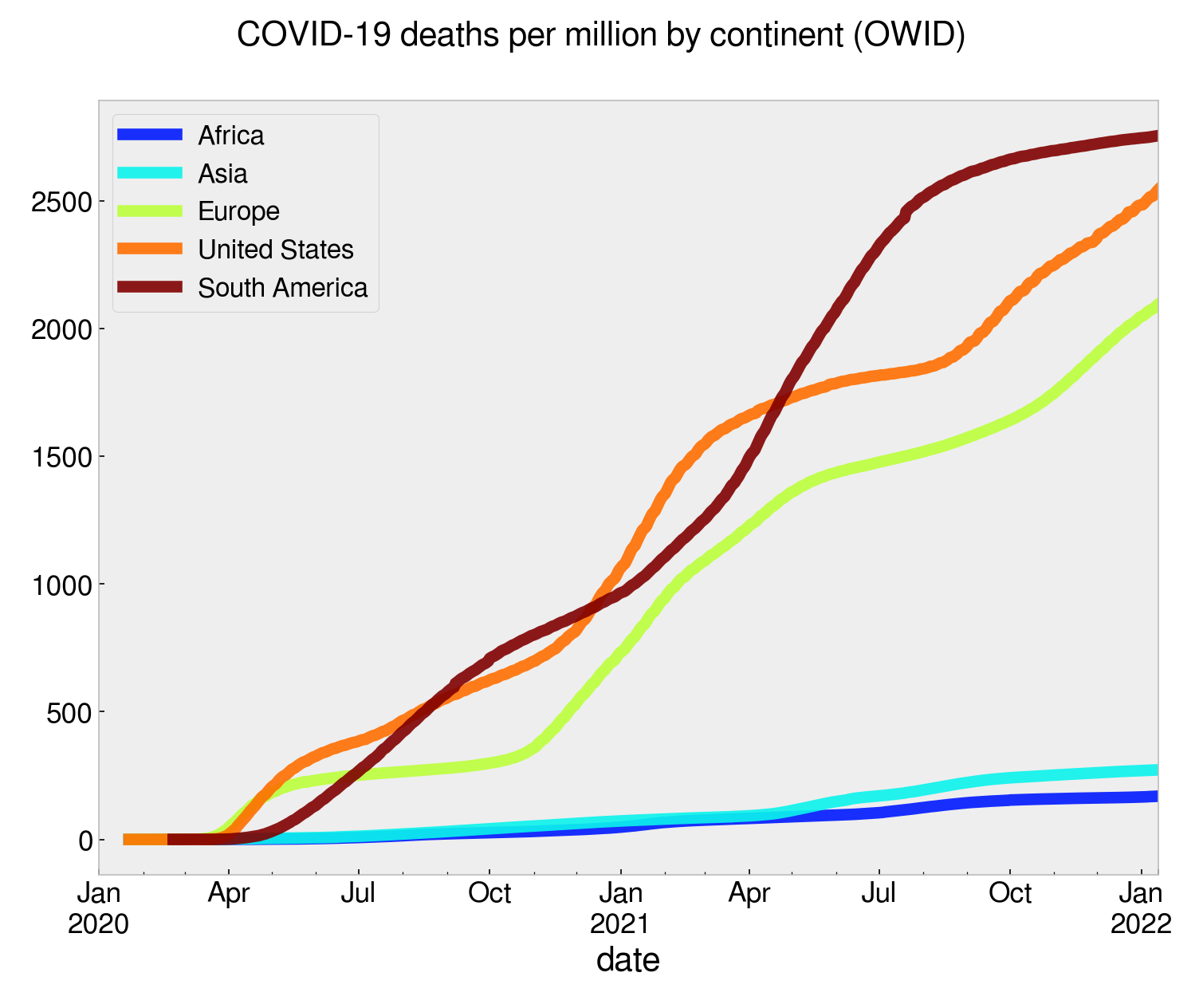

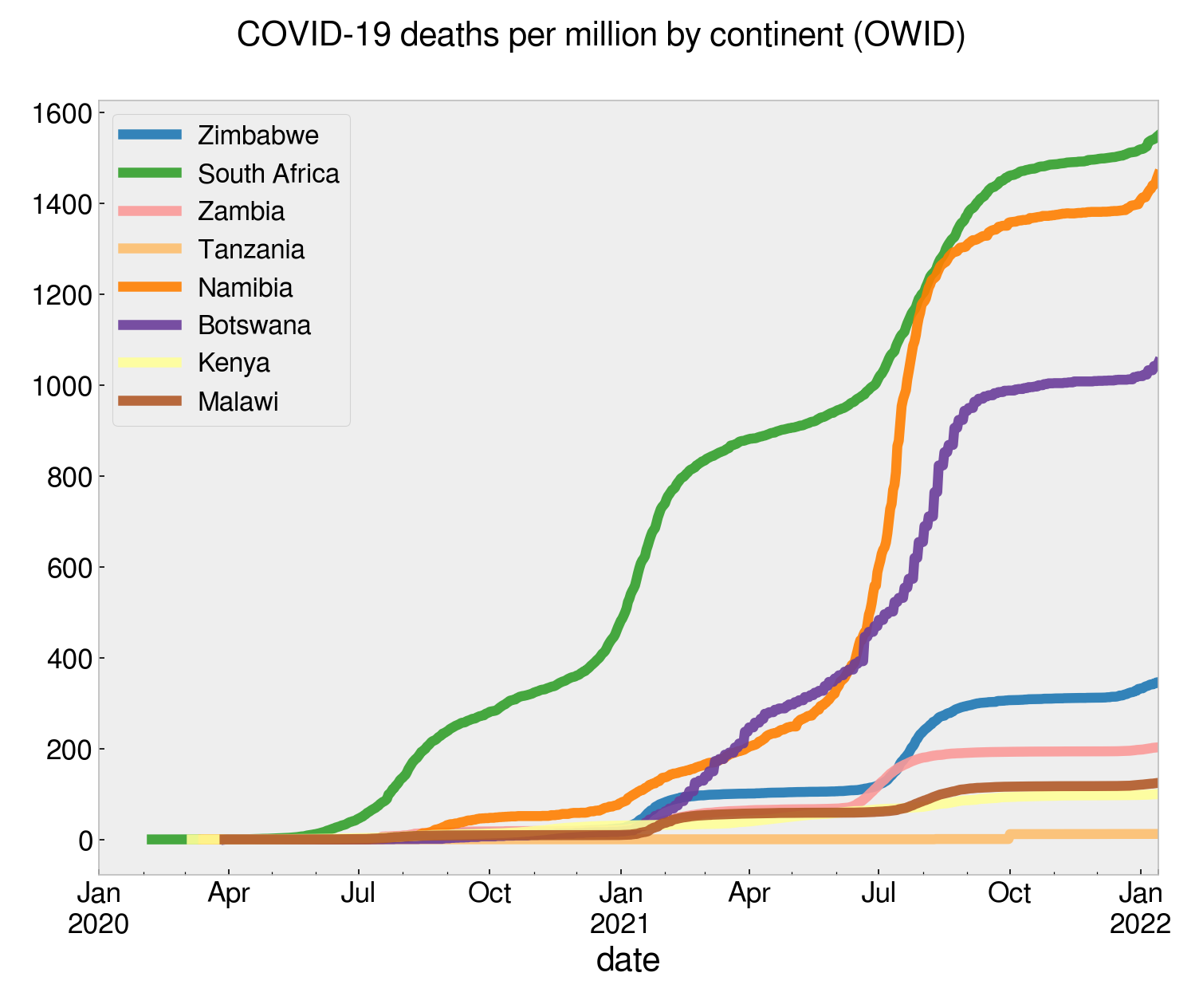

There are many obvious important differences between the ‘developed’ world and so-called low income countries. One is a generally much younger population age profile in most of Africa. We can see in the following graphs the contrast between African and European/US deaths per million from Covid. Even taking into account the likely under counting in some countries, deaths were far lower in regions with often inferior health systems. The true reasons are not actually obvious but the drastically lower susceptible very elderly people in Europe must surely be a major factor. The risk profile of Covid-19 is highly stratified by age. It is probable that over half the deaths from the disease were in nursing homes in Europe. South Africa had a markedly higher death rate compared to nearby countries as seen in the second plot. This could be partly due to counting but it does have an older age profile. There are always confounding factors to consider of course. South Africa also has a higher HIV prevalence than it’s neighbours for example.

Health priorities

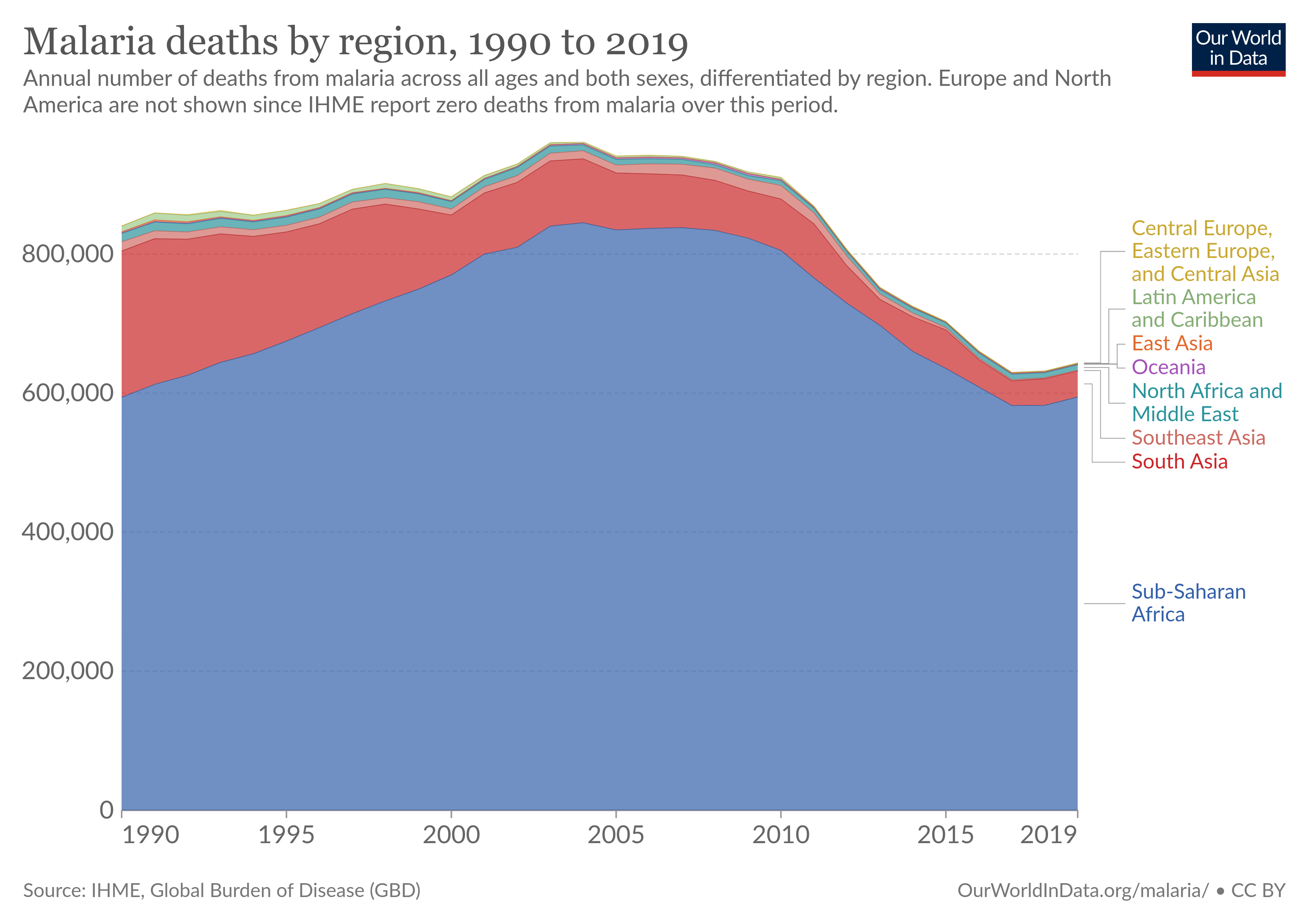

It need hardly be stated that healthcare priorities are entirely different throughout regions in Africa. There are radically different sets of endemic diseases, many of them affecting children, notably TB and malaria. Restrictions have seriously affected access to healthcare where these diseases can be treated or prevent by childhood vaccination. The WHO warned, as reported in the BMJ1, in 2020 that “malaria deaths caused by pandemic driven shortfalls in prevention and treatment efforts would probably dwarf direct deaths”. The yearly scale of malaria in the region is huge. In Zimbabwe alone 310,000 malaria cases were reported in 2019 according to the CDC. There was a surge of malaria deaths in the country in 2021. Suspension of insecticide-treated net distribution cannot have helped the sitation2.

The situation with TB is equally dire. It has been estimated that an additional 400,000 people may die globally from inadequate tuberculosis treatment as a consequence of these measures. A report by WHO and UNICEF in July 2021 stated that 23 million children missed out on routine vaccines in 2020 due to disruption or halting of routine services. 17 million of these children didn’t receive a single vaccine in the whole year. Much of this reduction was due to disturbances caused by pandemic restrictions, not the disease itself. In this regard it is worth reading Martin Kulldorffs’ Twelve Forgotten Principles of Public Health and ask how many of these principles have been violated in the past two years.

In short the health priorities in these countries are very different and to wholesale copy the lockdown policies of the rich West was surely self defeating.

Malaria deaths by region (OWID).

Zimbabwe

A case in point is Zimbabwe. Lockdowns are a perfect excuse for authorities to exert unwarranted control over the population in any country. In Zimbabwe, the measures were cynically used to curtail the right to protest throughout 2020 to silence journalists and opposition politicians. The 2020 Public Health Order (Statutory Instrument 83) introduced to enforce the lockdown includes totally unwarranted prohibitions on ‘false reporting’ and restrictions on protests, as discussed here. Article 14 of the Order punishes “any person who publishes or communicates false news about any public officer, official or enforcement officer involved with enforcing or implementing the national lockdown.” The government can simply state they are following WHO guidelines in response to any criticism. Zimbabwe is by no means the only country using the crisis to enact such legislation of course. (The UK government, for example, introduced the Policing Bill in March 2021 that threatens to criminalise the right to peacefully protest).

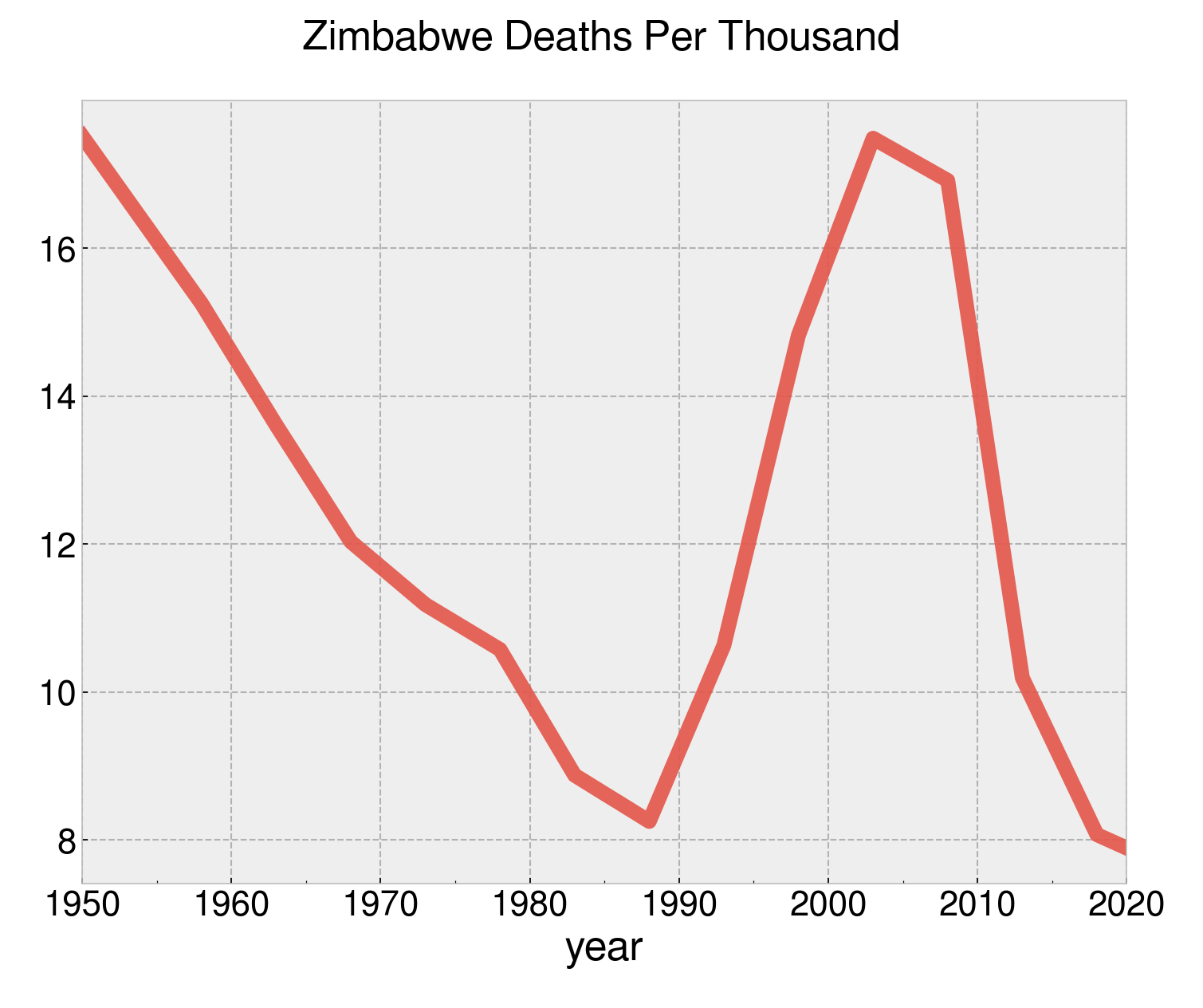

There were certainly an increased number of deaths due to Covid-19 in 2020/21. It may have even been under counted. But consider for a moment the plot below. It shows the all cause deaths per thousand trending in Zimbabwe since 1950. We can see the catastrophic increase caused by the AIDS epidemic and how long this took to return to previous levels with the advent of effective treatments. Covid-19 did not represent anything remotely like this threat. Note that accurate mortality data for 2020 has yet to be reported.

Zimbabwe death rate since 1950.

The government also decided to follow the example of many wealthy countries by closing schools throughout most of 2020. A phased re-opening occurred in 2021, this was dragged out and then further halted by teacher strikes. Schools are partly closed at the time of writing. Now many children have had limited access to school for almost two years with no possibility of even online learning. This will undoubtedly impact literacy rates for disadvantaged children. The Ministry of Education even resorted to radio and television lessons, ignoring the fact that many children don’t even have ready access to electricity or are out of transmission range! Power blackouts are common in Zimbabwe even in urban areas. The move to such online methods turns education into a preserve of the country’s elite, even more so than in Europe. Online learning is now recognised as a failure in affluent countries and is even more of a disaster for Zimbabwe. Instead of a strong push back against these policies, we see this kind of commentary by public health academics. In this letter to a journal called Public Health in Practice, the authors suggestions for addressing the education problem are risible. Nonsensical notions such as using Whatsapp as a substitute for in-person teaching should frankly be treated with the ridicule they deserve.

The Sustainable Development Goals

The following quote is from a Nature Editorial from 14 July 2020:

"All in all, the goals to eliminate poverty, hunger and inequality, and to promote health, well-being and economic growth are headed for extinction. In many instances, countries will be unable to even record what is happening: according to a survey of 122 national statistics offices by the UN and the World Bank, 96% of such offices have fully or partially stopped face-to-face data collection."

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of targets for the eradication of extreme poverty, delivery of improved education and healthcare with a particular focus on poor countries. They are included in a UN Resolution called the 2030 Agenda so have major international support. Goal 3 refers to good health and well being. The shifting of immediate focus of international agencies to a single disease has severely compromised these goals. If one reads the individual targets here it is evident that many of them are now virtually impossible to achieve by 20303. A revisiting of these goals has been suggested. It is to be hoped that any future frameworks will not be so easily compromised by such short sighted public health planning.

References

- African malaria deaths set to dwarf covid-19 fatalities as pandemic hits control efforts, WHO warns. BMJ 2020; 371 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4711 (Published 02 December 2020) BMJ 2020;371:m4711

- Gavi, S., Tapera, O., Mberikunashe, J. et al. Malaria incidence and mortality in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of routine surveillance data. Malar J 20, 233 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03770-7

- Fenner R, Cernev T. The implications of the Covid-19 pandemic for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals. Futures. 2021;128:102726. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2021.102726

Links

- Twelve Forgotten Principles of Public Health

- Lockdowns have killed millions

- For poor countries, lockdowns cost more lives than they save

- COVID-19 pandemic leads to major backsliding on childhood vaccinations

- Are UN’s Sustainable Development Goals in the Doldrums Due to the Corona Virus?

- COVID-19 and sustainable development goals (SDGs): An appraisal of the emanating effects in Nigeria

- A tale of two pandemics: the true cost of Covid in the global south

- Please stay out of Africa, Tony Blair

- Has the Great Barrington Declaration been vindicated?

- Effects of Lockdown Policies for COVID-19 in Mozambique