Finding all amino acid mutations in SARS-CoV-2

Background

Groups studying the SARS-CoV-2 virus are using genomes from GISAID to keep track of variants that could have functional effects on the virus phenotype. Some of them may be positively or negatively selected for. These genomes are updated daily from sequencing results across the world. There are at present ~8000 sequences for the human virus present. This data is available with free registration on the GISAID website.

One way of using these sequences is to calculate the number of non-synonymous mutations arising in the genome since the first identified isolate from Wuhan was sequenced. There is more than one way to do this as usual. Typically a phylogenetic approach is used using the nucleotide sequence. An alternate way is to annotate the genomes and extract the corresponding protein sequences across all non-redundant genomes (non-identical). Then these can all be aligned against the reference to see the amino acid substitutions. Here I use some code from a Python package I made called pathogenie to do the annotation. Notice that annotating all the genomes like this is somewhat inefficient since they are practically identical. However since they’re viral genomes it’s very quick and it lets us extract the sequence for any protein of interest. This approach would work for more distant sequences too.

Method

There were 7428 complete nucleotide sequences for SARS-CoV-2 sampled from humans present in the GISAID database at time of writing. These were reduced to 6408 by removing exactly identical sequences. They are annotated and the function returns a pandas dataframe of all proteins from all samples. From these we extract the orthologs by name (we could do it by sequence similarity too) and then collapse these to the unique set of protein sequences which will be much less. Finally we can compare each one to the reference to see the mutation(s). This is done by pairwise comparisons to the reference.

Annotations

First let’s check that our annotation works ok against the reference genome which is NC_045512. Here are the proteins in the NCBI RefSeq annotation:

| gene | locus_tag | length |

|---|---|---|

| orf1ab | GU280_gp01 | 7096 |

| S | GU280_gp02 | 1273 |

| ORF3a | GU280_gp03 | 275 |

| E | GU280_gp04 | 75 |

| M | GU280_gp05 | 222 |

| ORF6 | GU280_gp06 | 61 |

| ORF7a | GU280_gp07 | 121 |

| ORF7b | GU280_gp08 | 43 |

| ORF8 | GU280_gp09 | 121 |

| N | GU280_gp10 | 419 |

| ORF10 | GU280_gp11 | 38 |

Next we can annotate with my own routine as follows:

from pathogenie import app,tools

sc2,sc2recs = pathogenie.run_annotation('NC_045512.fa', kingdom='viruses')

Here is my annotation below. You can see there are some differences. We are missing the E protein and ORF10. ORF8 is there but without the gene name. My method probably needs improvement! Even automatic annotations will not be the same. However it’s good enough that we can use this for the reference proteins, since most of the proteins are present and the sequences should be identical.

| gene | product | length |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Replicase polyprotein 1a | 4388 |

| rep | Replicase polyprotein 1ab | 2595 |

| S | Spike glycoprotein | 1273 |

| 3a | Protein 3a | 275 |

| M | Membrane protein | 222 |

| 7a | Protein 7a | 121 |

| N | Nucleoprotein | 419 |

| - | hypothetical protein | 43 |

| - | hypothetical protein | 121 |

| - | hypothetical protein | 51 |

Some code

Imports:

import pandas as pd

from Bio import SeqIO,AlignIO

from Bio.Seq import Seq

from Bio.SeqRecord import SeqRecord

import pylab as plt

import pathogenie

All of our sequences from GISAID are in one file and some have the same id. This method allows us to load sequences from a fasta with duplicate sequences:

def load_deduplicated_sequences(filename):

"""Load a fasta file of sequences and ignore duplicates"""

newrecs = {}

unique_seqs=defaultdict(list)

with open(filename, 'r') as in_handle:

for rec in SeqIO.parse(in_handle, "fasta"):

if rec.seq in unique_seqs:

continue

if not rec.id in newrecs:

try:

id = rec.id.split('|')[1]

newrecs[id] = rec

unique_seqs[str(rec.seq)] = id

except:

pass

return newrecs

Here’s the method used to get the mutations from the protein sequences. Pairwise comparisons are used so the record can be stored with the mutation name.

def get_mutations(recs, ref):

mutations = {}

positions = []

for rec in recs:

aln = pathogenie.clustal_alignment(seqs=[ref, rec])

#print (aln)

for pos in range(len(aln[0])):

refaa = aln[0,pos]

aa = aln[1,pos]

if aa != refaa:

#print (refaa, aln[:,pos], aa)

mut = refaa+str(pos+1)+aa

mutations[rec.seq] = mut

positions.append(pos)

return mutations

This is the code that runs the whole process. We can run this for each protein by providing the reference version and all the records (with nucleotide sequences). Note that the annotation is run once and the result passed to the function. The other methods used here are not shown in detail. The code for those methods can be found on the github repo for pathogenie here.

#run the annotation

gisrecs = load_deduplicated_sequences('gisaid_cov2020_sequences.fasta')

annot = pathogenie.annotate_files(gisrecs, outdir='gisaid_annot', kingdom='viruses')

names = ['Protein 7a', 'Protein 3a', 'Spike glycoprotein','Membrane protein',

'Nucleoprotein','Replicase polyprotein 1a','Replicase polyprotein 1ab']

res=[]

mutant_seqs = {}

for protname in names:

refprot = sc2[sc2['product']==protname].iloc[0]

refrec = SeqRecord(Seq(refprot.translation),id='ref')

print (protname)

annot_seqs = pathogenie.get_similar_sequences(protein, annot)

unique_seqs, counts = pathogenie.collapse_sequences(annot_seqs, refrec)

print ('%s unique sequences' %len(unique_seqs))

mutations = get_mutations(unique_seqs, refrec)

#convert mutations to string and count the frequency

muts = {seq:'+'.join(mutations[seq]) for seq in mutations}

#save the sequences for later use

mutant_seqs[protname] = muts

freqs = [(muts[seq], counts[seq]) for seq in muts]

#convert freq table to dataframe

fdf = pd.DataFrame(freqs,columns=['mutation','count']).sort_values('count',ascending=False)

fdf['protein'] = protname

print (fdf[:10])

res.append(fdf)

res = pd.concat(res).sort_values('count',ascending=False)

Results

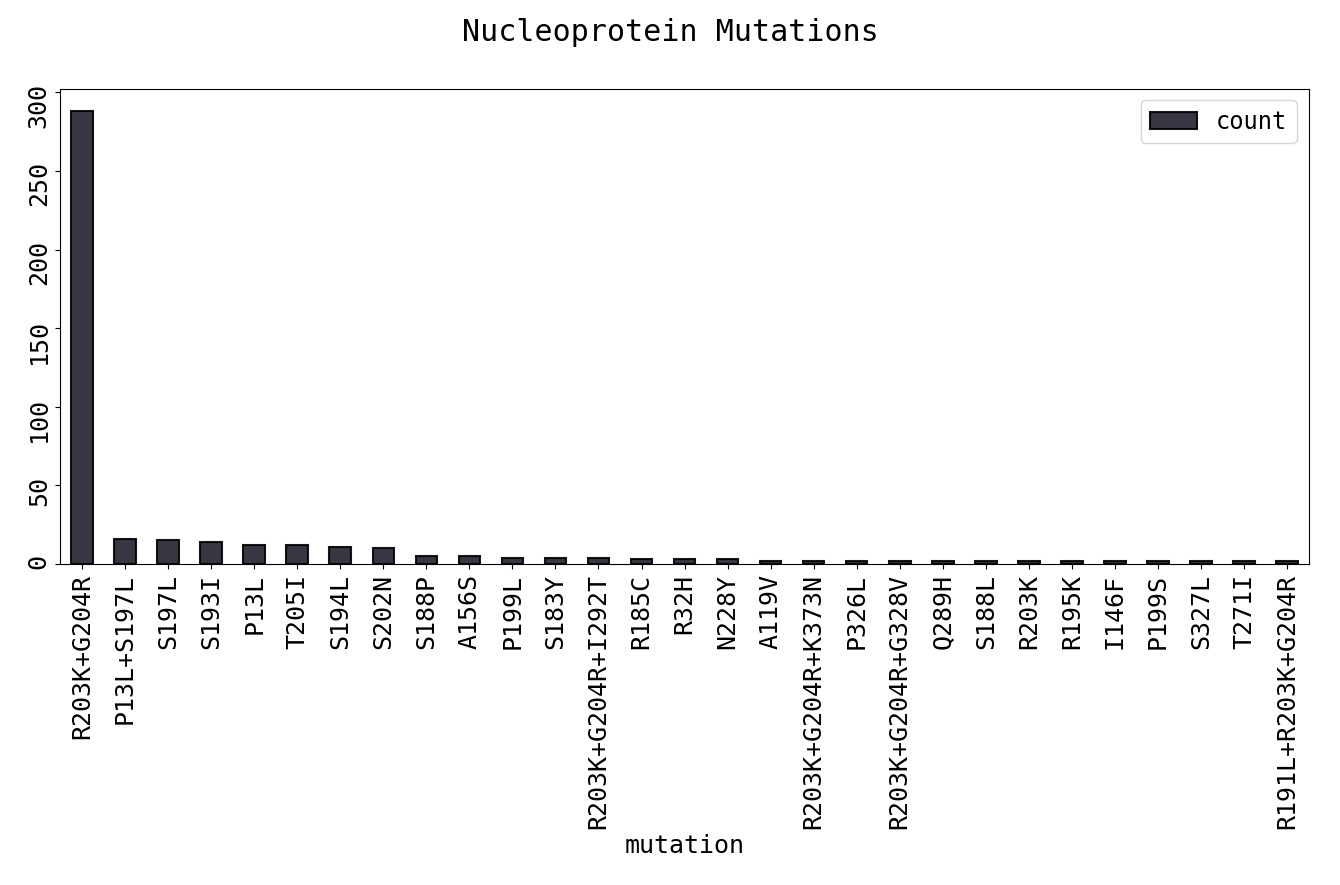

The output, as would be expected, is a large number of rare substitutions that appear only once or several times and a very few common mutations that have been fixed in the population. The rare mutations could be more recent, random for the particular isolate or possibly even due to sequencing error. This is indicated in the plot of the top mutations in the N protein:

The top 15 most frequent mutations are below. D614G in the Spike glycoprotein is by now a well known mutation. As is R203K+G204R in the Nucleoprotein, which is present in one third of reported sequences from Europe. This polymorphism is predicted to reduce the binding of an enclosing putative HLA-C*07-restricted epitope, an allele common in Caucasians.

| mutation | count | protein |

|---|---|---|

| D614G | 792 | Spike glycoprotein |

| P214L | 769 | Replicase polyprotein 1ab |

| Q57H | 386 | Protein 3a |

| R203K+G204R | 288 | Nucleoprotein |

| G251V | 225 | Protein 3a |

| P1327L+Y1364C | 222 | Replicase polyprotein 1ab |

| T248I | 165 | Replicase polyprotein 1a |

| L3589F | 61 | Replicase polyprotein 1a |

| T175M | 46 | Membrane protein |

| I722V+P748S+L3589F | 44 | Replicase polyprotein 1a |

| D431N | 38 | Replicase polyprotein 1a |

| D3G | 33 | Membrane protein |

| G196V | 28 | Protein 3a |

| F3054Y | 27 | Replicase polyprotein 1a |

The file with all mutations is found here. As you can see this is a non-phylogenetic method and has limitations as such. We can’t easily see from this which clade the mutation exists in for instance or when it initially appeared. It hopefully illustrates that there are multiple alternative methods to achieve similar goals in genomic analysis.