Sequence, gene and protein databases: are you confused?

So many databases

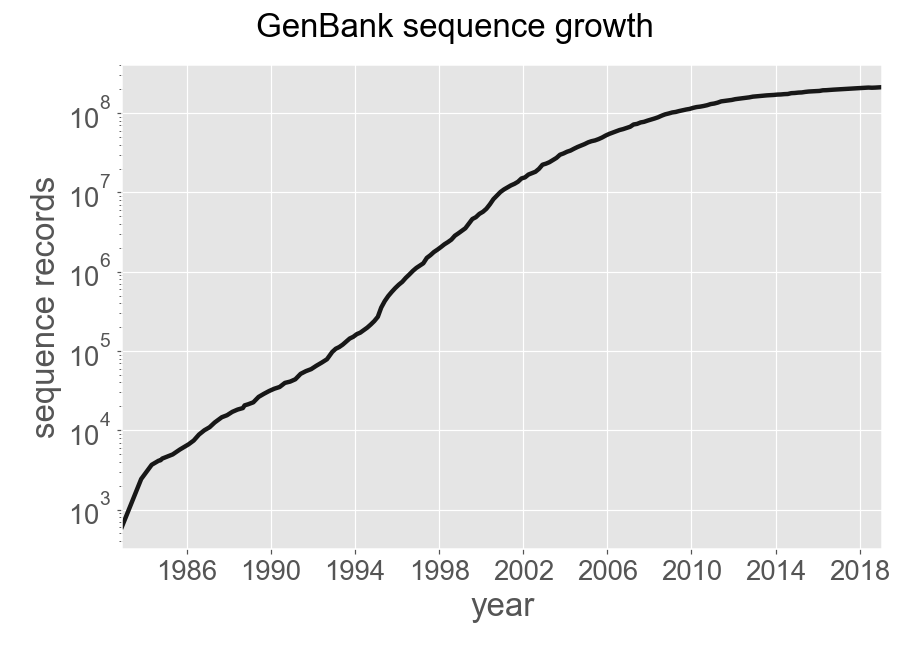

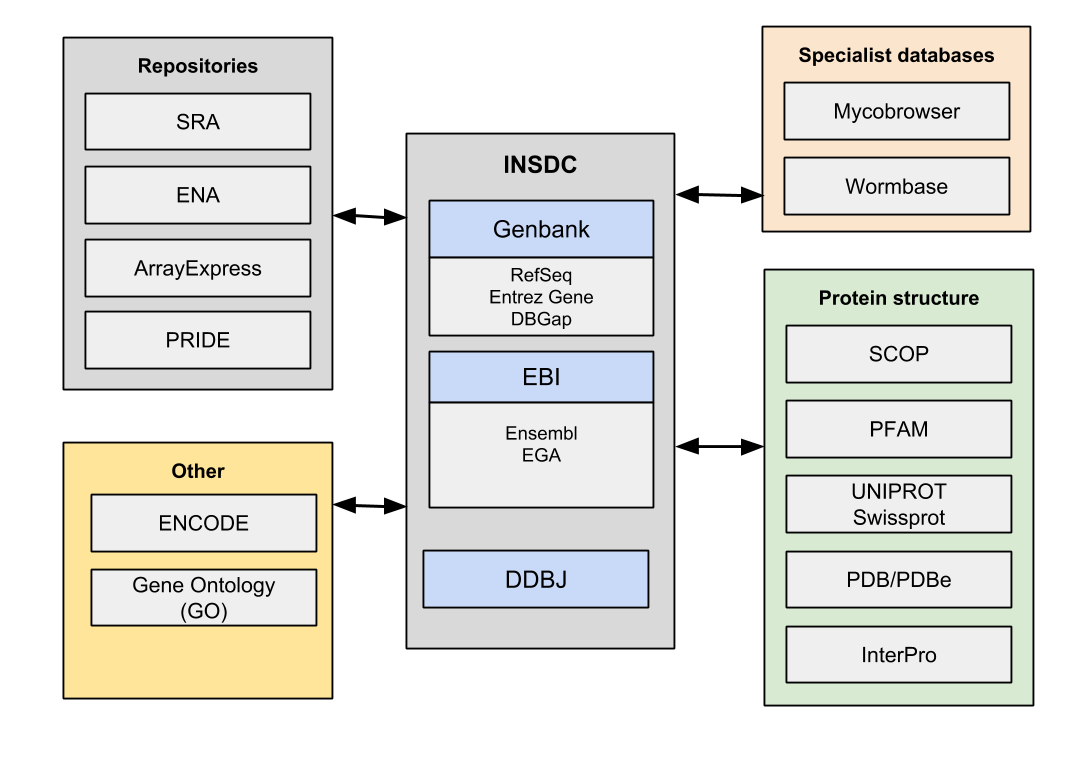

Advances in sequencing technologies over the last two decades has meant a huge increase in the amount of raw sequence data. GenBank has grown rapidly, at times at an exponential rate, as seen below. The management of genomic data is founded on the existence of the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC). This is a consortium of three databases, DDBJ/ENA/GenBank, that operate independently but synchronize their data. From this primary source of sequence data many other secondary and tertiary databases are constructed. These provide much more specific purposes and feed data back and forth to the main databases. Genes are linked using unique identifiers.

The profileration of so many sub-databases with linked datasets is bewildering even for experienced biologists. It is clearly a serious challenge for the average user to make sense of both the data itself and associated web interfaces. A short overview of some of these databases and the distinction between them is given here.

SRA, ENA and ArrayExpress

The Sequence Read Archive (SRA) is the INSDC project for storage of raw sequence data from next-generation sequencing platforms such as the Illumina platform. This includes data from RNA-Seq and ChIP-Seq studies. Data is often uploaded as aligned BAM files. You can use the NCBI SRA Toolkit to fetch data using accession numbers. Deposition of data in the SRA is mandated by most funding agencies and many journals. The European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) are the sequence repositories managed by the EBI and stores EMBL-bank, their instance of primary nucleotide sequences discussed above. It also runs an instance of the SRA. You can upload raw reads to either platform. ArrayExpress stores functional genomics data from various modalities like RNA-Seq. It includes a web-based submission tool called Annotare.

BLAST

Almost all molecular biologists will know about Blast, a sequence match algorithm. When you use the NCBI Blast service you are essentially searching the INSDC sequences for matches. This is a huge amount of search space and Blasts uses a form of caching so you get the results quickly.

Ensembl vs Entrez Gene

I suspect that these two terms are commonly mixed up. Ensembl is a joint project between EMBL-EBI (European) and the Sanger Institute to develop a software system annotation on selected eukaryotic genomes. Entrez is name of the NCBI infrastructure which provides access to all of the NCBI (US) databases. That includes PubMed, SRA etc and the Gene database (Entrez Gene). Both are built on INSDC and you could say annotate the same data in varying ways. You can therefore map a gene with an Ensembl ID to and Entrez gene name though the process is not as clear cut as you might think. Many people prefer to stick to one annotation source and always use Entrez only.

The websites also look quite different. Both have genome browsers. As to which website is easier to use is a matter of preference. As an example compare these two pages on Ensembl and Entrez gene for the BRCA2 gene. Both have very similar information.

CCDS

The NCBI/Ensembl/Havana annotations of genes may use different methods and result in non-identical information for the same gene. The long term goal is to support convergence towards a standard set of gene annotations. The Consensus CDS (CCDS) project was established to assist this goal for mouse and human genes which are the most complete genomes. You can use the website to check a proteins’ matching entries between the databases.

BioMart

This is basically a database (‘market’) of databases. It’s a way for databases to make their info available using a standard set of tools. You can use languages like R via the biomaRt package to access many datasets this way. Ensembl provides their Mart (Ensembl BioMart) via a web interface that allows you to build gene id mappings between their Ensembl IDs and many other identifiers linked in other databases.

UniProt

This is a protein centred database that integrates sequence information with structural annotation. This is both human curated and automatically derived (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot). Much of the functional annotation is manually added by scanning the literature. You would typically use UniProt to find what protein information is available for your gene and do comparative analysis to similar proteins. UniRef is a non-redundant dataset used to combine the protein sequences into clusters at 90 and 50 percent sequence identity. This can make searches much faster.

The PDB

A major source of data for UniProt is the Protein Data Bank, a database for the three-dimensional structural data of large biological molecules. Structures are solved experimentally by X-ray crystallography or NMR and stored as 3D atomic coordinates. These structures can be viewed in 3D viewers in the web page or downloaded as pdb or mmCIF files and viewed with programs like PyMOl. They are linked to their protein sequences on UniProt and GenBank.

PFAM, SCOP and CATH

Since proteins are conserved across species they can be grouped into families by sequence, structure or function. PFAM is a database of protein families based on UniProt reference proteomes. It uses hidden Markov models (HMMs) to classify proteins into related groups at levels of family/domain/repeat/motifs. The classification schemes CATH and SCOP were created for the evolutionary relationship specifically of protein domains. They use different but complementary methods to classify the Uniprot data. InterPro is an EMBL-EBI project that integrates these and other classifications into a single resource. Structural identity is much more sensitive than sequence. Blast rarely finds homology between two sequences having less than 30% identity. However, some proteins have the same structure, despite having much lower sequence identity. Using these tools, you can see how quickly you could take an unknown new protein and find out to which family it might belong, even if a Blast returns no close orthologs. Another application is in predicting which domains your protein might bind to.

Specialist databases

Many other databases obviously exist. At some point it seems there was a database created for each paper published. Some are small and dissapear in a short time. The large specialist databases are quite important however, some having institutional support which is required for longevity. One of these is WormBase, the nematode resource. Sort of like the Ensembl for Worms. These databases are maintained by researchers specific to the topic and are often genome assembly/annotation projects that submit their data to INSDC ultimately.

Down a rabbit hole

Those trying to find information in one of these websites might find themselves daunted by all the links and going round in circles. It’s worth looking at a brief guide to what the website does or a video tutorial before trying to tackle something like Ensembl. These interfaces could still certainly be improved in terms of usability but there is a huge amount of functionality available - if you have the time to learn how to use them..

Links

References

- Maglott D, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, Tatusova T. Entrez Gene: gene-centered information at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;39(Database issue):D52-7.