Analysis of MTBC regions of difference with NucDiff

Background

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) is the causative agent of human TB. Not only are there are multiple closely related lineages of the bacteria present in human populations, there are also animal adapted organisms, such as M. bovis, that infect a broad range of animal species beyond their most prominent host in cattle. The entire group is referred to as the M. tuberculosis complex (MTBC). The animal adapted species are characterized by high sequence similarity (>99.9% identity) to MTB but with key sequence polymorphisms called regions of difference (RDs) in which deletions or insertions are present. Some of these may be important for adaption to the chosen niche of the species. But the ecology and the evolution of these animal-adapted species are poorly understood, with only a few representatives having been isolated so far.

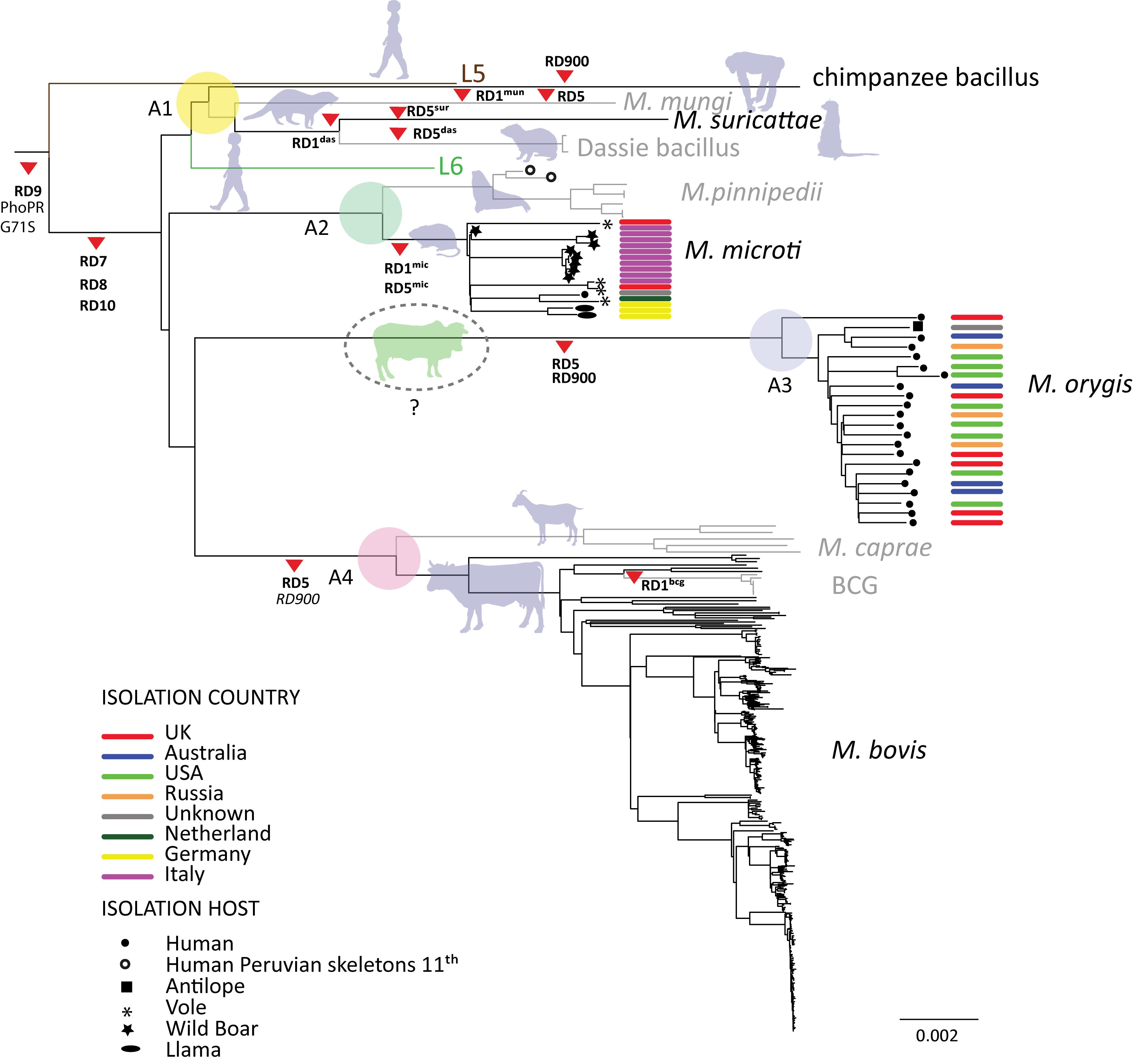

With the increased use of whole genome sequencing it’s now possible to compare many genomes together across their entire sequence. This is usually done by aligning the sequence reads to a reference genome (H37Rv) and calling variants. SNPs are filtered and then used to build a phylogeny. This is how the tree on right was made in a recent paper (Brites et al., 2018). This tree also shows the clades some of the major deletion events. These were determined by annotation of unmapped reads (those with no coverage to the reference).

Region of difference detection with NucDiff

A previous post detailed how NucDiff can be used for pairwise genome comparisons to detect sequence polymorphisms from assemblies. It uses MUMmer for aligning genomic sequences and NucDiff which parses the results. NucDiff locates and categorizes the differences and saves them in gff files that can be viewed in a genome browser. This is another approach to RD detection that might be useful as an addition or alternative to the above read mapping method.

Example: M. orygis

M. orygis is a relatively newly defined lineage (clade A3 in the figure) whose host range is not well known but appears to mainly infect cattle in Asia. It is closely related to M. bovis and M. caprae. We wanted to show any common differences shared between these clades. As an illustration of the possible functionality of this approach, assemblies from a representative group of orygis and other MTBC isolates were run their results grouped together.

RD8: 4057733-4063249, (EphA-lpqG)

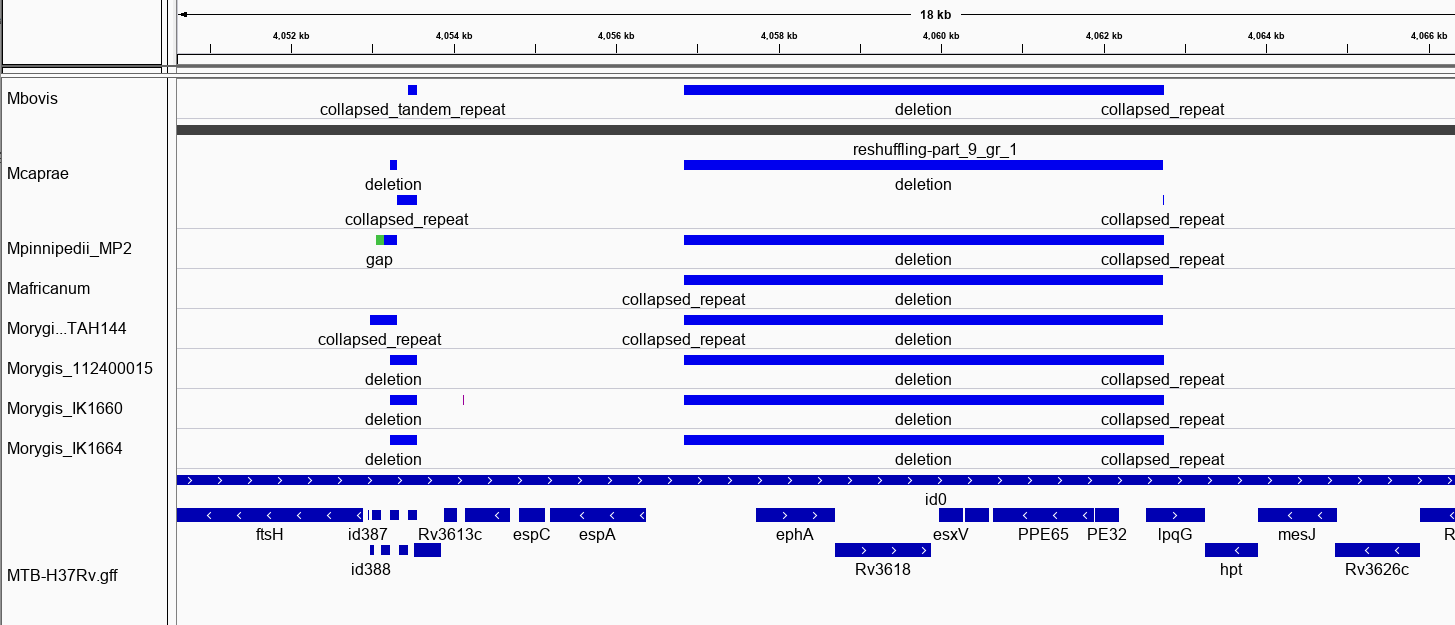

The program produces gff files that you load into a genome viewer in tracks. This is shown below for RDB, a change common to all MTBC animal clades. The track on bottom are H37Rv gene annotations. NucDiff has correctly detected this deletion.

gyrB mutations

It’s also possible to detect SNPs with NucDiff. We can see below that two of the known mutations common in animal adapted MTBC species are found here. One is a G->A mutation in gyrB only found in the M. orygis lineage.

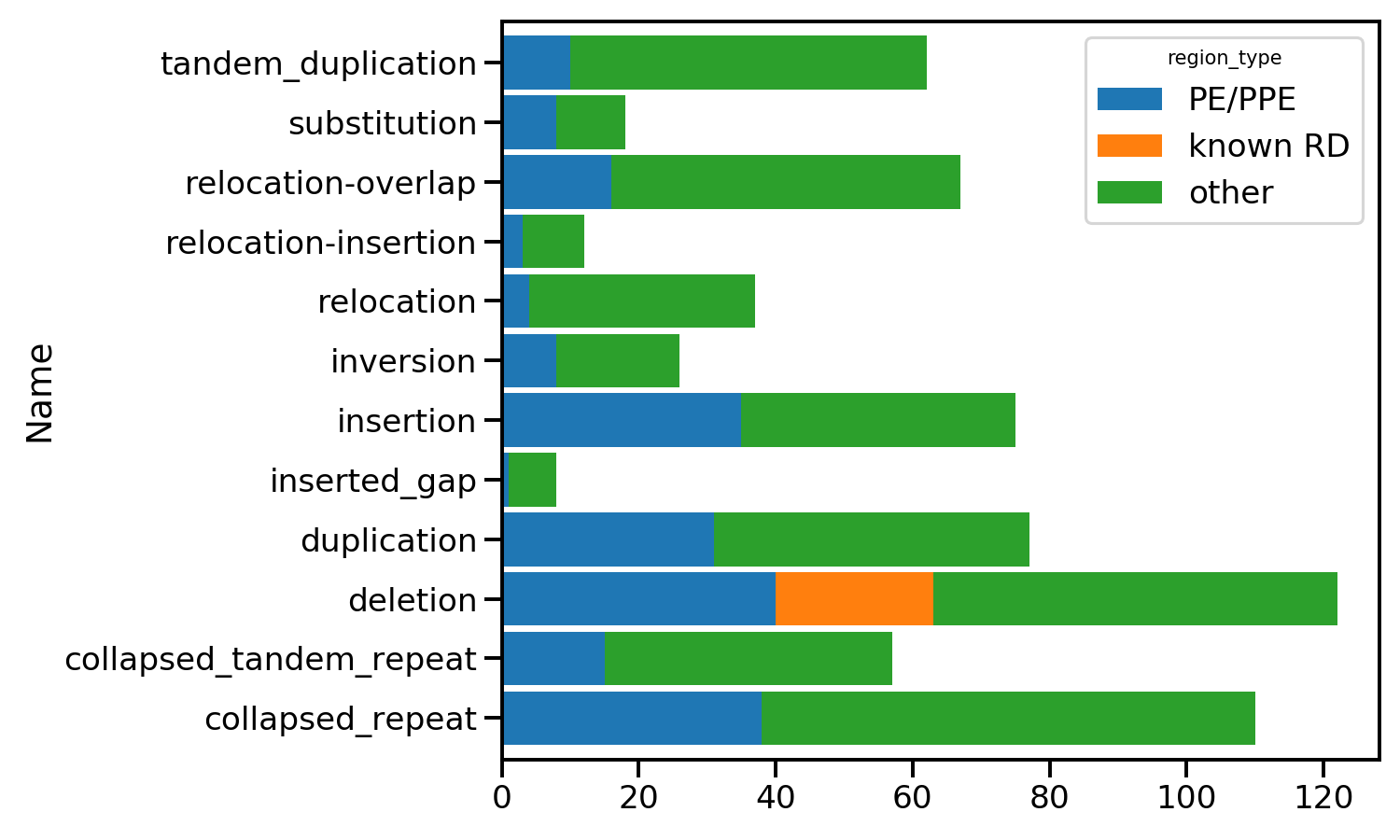

Many changes in PE/PPE regions

When we group together all the unique differences over the isolates we get a picture of the types of changes detected. They are shown below grouped by category. Those in PE/PPE proteins can often be discounted as they are proteins containing repeats giving rise to sequencing artifacts.

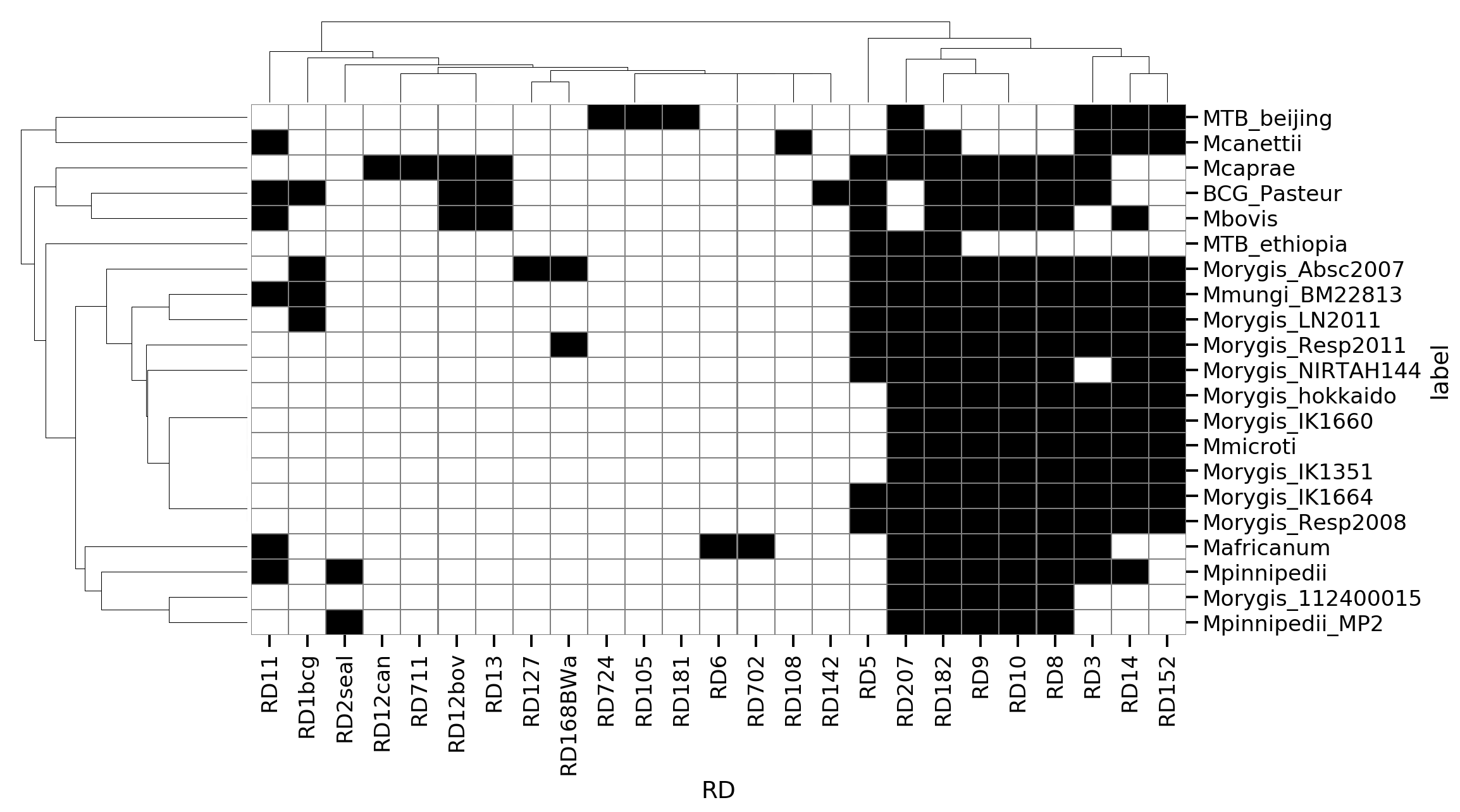

Known RDs

We can also detect the overlap of our indels with the set of known RDs using their coordinates. This was used to make the matrix below indicating presence/absence of RDs for each isolate. This appears generally consistent with a few exceptions.

RDoryx_wag22 deletion

This deletion is specific to M. orygis but was not correctly detected as the contigs in the assemblies do not cover the gap, as shown below. The change is instead marked as a relocation at the edges of the contigs. This shows the possible limitation of the method if you are looking for deletions. Using some form of reference guided assembly seems to solve this problem as you can join contigs based on a known closely related genome and then detect the gaps. Using reference guided assembly might introduce other artifacts in the genome though.

Usefulness

This method could be used to discover novel polymorphisms common across multiple strains. However it is subject to the quality of assemblies in some cases and some deletions might be missed. Though this may only be the larger ones. Reference guided assembly of your isolates might be a way to improve detection of these.

MTBdiff

You can run your own samples from the command line using the Python package mtbdiff to try this out. The code to make these plots is available here.

Links

References

- Brites, Daniela et al. “A New Phylogenetic Framework for the Animal-Adapted Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex.” Frontiers in microbiology vol. 9 2820. 27 Nov. 2018, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02820

- Faksri, Kiatichai et al. “In silico region of difference (RD) analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from sequence reads using RD-Analyzer.” BMC genomics vol. 17,1 847. 2 Nov. 2016, doi:10.1186/s12864-016-3213-1

- R. Brosch, S. V. Gordon, M. Marmiesse, P. Brodin, C. Buchrieser, K. Eiglmeier, T. Garnier, C. Gutierrez, G. Hewinson, K. Kremer, L. M. Parsons, A. S. Pym, S. Samper, D. van Soolingen, S. T. Cole. A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Mar 2002, 99 (6) 3684-3689; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.052548299

- Mostowy S, Inwald J, Gordon S, et al. Revisiting the evolution of Mycobacterium bovis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(18):6386–6395. doi:10.1128/JB.187.18.6386-6395.2005

- K. M. Malone and S. V. Gordon, “Strain Variation in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex: Its Role in Biology, Epidemiology and Control,” in Adv. Exp. Med. Biol., vol. 1019, 2017, pp. 79–93.